Reflections on the EUvsVirus hackathon as an ad-hoc innovation site

by Julia Renninger (TUM). These reflections are part of a larger case study on the EUvsVirus hackathon, which will be published in summer 2021.

From April 24-26, the European Commission hosted the EUvsVirus hackathon to “hack the crisis”. Part of a wide array of crisis responses in Europe, the hackathon was seen as a particularly promising, co-creative act of harnessing the ideas and talent of experts alongside EU citizens usually not involved tackling policy and innovation challenges. Co-creation – the practice of bringing together diverse innovation actors to produce better, more sustainable, and socially robust innovation outcomes – is en vogue as an approach to tackling complex innovation challenges. SCALINGS has studied many co-creation practices yet EUvsVirus revealed a completely new format of co-creation to us, as:

- It was brought to life as an ad-hoc crisis response in the midst of a global pandemic, by a small group of EC policy officers and 400 quickly assembled volunteers.

- It was digitally rolled out on a massive scale with approximately 25,000 participants submitting a total of 2,164 projects/solutions with the goal to “hack” a range of Corona-induced challenges and deliver results in no time.

As a group of researchers used to analyze “slow” co-creation practices for months and months in other case studies, for this one we had exactly 48 hours to register, participate, hack, observe, take notes, record meetings, and hack some more. Questions at the heart of SCALINGS are not easily answered within this given time frame, such as: How is innovation framed, by whom, how do involved actors pre-configure roles, co-creation processes and end products? The richness and intensity of our hacking experiences still uncovered limits of the format “hackathon” as an enabler of responsible innovation “for the good of all”.

Are we hacking as citizens or entrepreneurs?

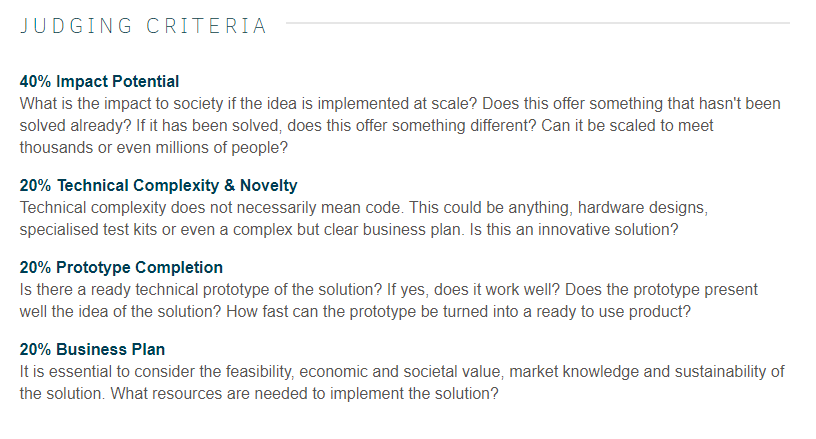

One key question that emerged quickly for us was whether our expected role as a hacker was that of a citizen or an entrepreneur. Or, as a citizen with an entrepreneurial mindset? Or an entrepreneur with an eye for citizen needs? EUvsVirus was originally promoted by the EU Commission as “open to everyone”, and thus all people, with or without specific programming -or business skills as it might be the norm in other Silicon Valley type hackathons. But while EUvsVirus intended to attract a diverse set of participants, this ambition was not fully reflected in its setup. The judging criteria (see picture 2), for example, made it clear that specific skills would be needed to meet the expectations of the jury.

In what we saw, instead of allowing diverse in- and outputs, the hackathon encouraged its participants to produce MVP’s (“minimal viable products”), business plans and video pitches. On DevPost, the matching platform that was used to connect teams with specifically skilled team members, one could primarily add IT -or business related skills to their profiles, e.g. “JavaScript”, “SQL”, or “blockchain”. These options pre-framed the skills needed for the hackathon and, as a result, participants who did not fit into this frame were excluded or at least hindered from contributing solutions to the hackathon. These could be less tech-savvy participants from other disciplines, sectors and simply with skill sets that do not naturally come in handy in hackathons. If these groups are underrepresented and/or do not have the space to bring their needs to the table, the solutions emerging from EUvsVirus might come with gigantic blind spots.

Especially “Non-techies” could add value to teams by asking questions that might usually be skipped altogether: Why is a new technology the key to solving this issue in the first place? Who benefits from this technology? Who will be negatively affected if this solution is rolled out on a global scale? What kind of future is this solution creating, and who decides what a “desirable” future for the EU and beyond looks like? As a group of researchers that has studied in depth the challenges of meaningful co-creation practices, we are certain that these questions do not come with an easy answer and a 48-h hackathon could at most serve as a preliminary starting point to address them. The intention to include citizens into the process is, however, a first essential step that needs to be reflected in the hackathon design to fully live up to its promise. Especially against the backdrop that the European Commission increasingly pushes forward a more active role of citizens in innovation processes, as the name of the SCALINGS Horizon 2020 funding call “Science With and For Society” suggests.

The “Hack” in Hackathon

Further, the slightly blurry definition of what “hacking” meant took a toll on the hacking experience. It was not entirely clear how much hacking within the 48-h timeframe was needed to be able to call yourself a winner. In fact, some of the teams had not formed during the hackathon itself, but beforehand in a more or less professional setup. They might have participated in a previous national hackathon and now used this pan-European pendant to take their idea to the next level. Or they constituted a startup that tried to make their idea “fit” the corona crisis. To illustrate this with an example: One of us joined a team with two programmers from Romania that started building an “Uber for employees” a year ago. Their idea was to make co-workers share their commute in private vehicles to reduce traffic. EUvsVirus then changed their narrative and they claimed to build an app that not only reduces traffic, but also the risk of spreading the coronavirus. This raised some concerns about fair game in the judging procedure:

They have distorted and corrupted the meaning of “hack” in hackathon. This was just an innovation contest announced on short notice with the sexy little title hackathon to draw media attention… and they misled thousands of honest, hard working people to spend a whole weekend, sacrificing from family, etc. … to find out it was all for nothing really!

Anonymized hacker post in the #eucommunity slack channel

This statement, posted on the #eu-community slack channel by one participant, shows that it was not necessarily considered fair to judge already elaborate ideas from established teams in the same way as patchy first prototypes developed by scrambled together strangers. While there is always the possibility of having pre-existing startups hijack the hackathon as a platform to acquire new, skilled team members, get access to discounted software tools or a shot at winning the prize money, it left initially enthusiastic participants with a bitter aftertaste and the question why it was called a “hackathon” at all.

Hacking one united pan-European community as an end in itself

The previous two observations, however, would only matter if EUvsVirus was geared at detecting the most competitive solutions in the most ‘efficient’ way possible. But in addition to the competitive nature of the hackathon, EUvsVirus was striving to build a united community of European citizens (and beyond). In many of the emoji-heavy slack announcements, participants were celebrated for being part of one pan-European community and encouraged to share their countries’ flag as well as pictures of themselves “hacking in pajamas” (picture 1). Similarly, Facebook live streams started with jazzy hip hop tunes in the background and the two moderators sit-dancing and giggling into the camera asking “how little did you sleep last night?” (picture 3).

The actual production of results didn’t seem to matter as long as participants enjoyed the weekend and produced fun material for social media that represented the hackathon as a sort of EU-driven ‘anti-corona-festival’. In addition, a rather improvised organizational setup, noticeable for example in the hectic matchmaking process of teams with their mentors, led us to assume that the overall scale of the event that pushed the event’s community spirit, actually interfered with its smooth operation. After all, the coordination of around 25,000 people in a slack channel, several of which registered on the day the event started, is not an easy task.

This hints to the question whether the hackathon as a community and scale-driven innovation site “fits” well as a response tool to the corona crisis. Or, in other words, if the corona crisis serves as a “challenge” to be solved by a pan-European hackathon and the hacking culture that comes with it. Besides helping around 120 winners to connect with companies and institutions in the successive “matchathon”, for most participants EUvsVirus mainly constituted an anchor point of optimism and solidarity in a time of greatest uncertainty and isolation. Winning then becomes secondary and what matters is the feeling of “we are in this together”. Just a few hours upon registering one of our researchers was matched with a team working on a 3D printing app and suddenly found herself in a video call with people from France, Austria, Poland, and Spain. None of them had ever met before, and they exchanged smiles, corona anecdotes and first hacking ideas. Although the produced solution did not convince the jury, the co-creation experience in itself was perceived as an enriching experience, rewarded with a handful of new LinkedIn contacts that will hopefully outlive the hackathon. So, in case the hacking product did not unfold the desired impact in the fight against Covid-19, at least the hacking process served as a refreshing distraction from the humdrum life under lock-down.